What's a Christmas Concerto? Why is "Greensleeves" a yuletide classic? Why was the "Silent Night" so silent? Read on.

Corelli's Christmas Concerto

Calm and refreshing, a peaceful respite, Arcangelo Corelli’s “Christmas Concerto” (Concerto Grosso in G minor, Op. 6, No. 8) is just right for the holidays.

What is a Christmas concerto, you ask? Its characteristics are twofold: first, it’s a concerto grosso, meaning it’s a piece for several soloists accompanied by an orchestra. Second, one of the movements must be a Pastorale — music that recalls the shepherds of Bethlehem (watching their flocks by night, as it were). Often, the Pastorale imitates the sounds of old Italian shepherds’ instruments, like various pipes and bagpipes one might hear in the Sicilian countryside.

While practically every baroque composer wrote their own unique Christmas concerto, Corelli’s is one of the finest. Widely recognized as the father of the concerto grosso, Corelli was a true master at his art, and nowhere is it more apparent than in the calm and lovely atmosphere he creates.

Corelli also saves his Pastorale for the final movement, a glittering jewel that sets off the rest of the piece.

Watch a performance of Corelli’s Christmas Concerto with the Accademia degli Astrusi, led by conductor Federico Ferri:

Greensleeves / What Child is This?

A child, whose parents are turned away by the innkeeper, is born in a stable among animals.

Sound familiar?

The now-famous “What Child Is This?” has a storied history: Sir John Stainer combined a popular 16th-century English folk tune (“My Lady Greensleeves”) — a love song with far-from-religious roots — with three verses from William C. Dix’s “The Manger Throne.”

Dix, an insurance manager, had written the poem in 1865 as he recovered from an illness, highlighting the Christmas child’s humble beginnings, born among animals and soon greeted by shepherds:

What child is this, who laid to rest

on Mary’s lap is sleeping? Whom

angels greet with anthems sweet,

while shepherds watch are keeping?

The English carol first appeared in print in 1871. Listen to a classic take from The Choir of Kings College, Cambridge, directed by Stephen Cleobury:

Es ist ein Ros' enstsprungen

One of our favorite Christmas carols combines floral, biblical, and solstice references with sumptuous 17th century German choral music.

Written in 15th century Germany, the text to “Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming” (Es ist ein Ros’ entsprungen) is based on a biblical verse, referencing the lineage of the promised child as a branch growing out the stem and roots of Jesse.

The birth of the promised one, now referred to as a blooming rose, occurs during the Winter Solstice (“Amid the cold of winter, When half spent was the night”). While the composer of the melody is unknown, the gorgeous harmony is attributed to German composer Michael Praetorius (1571-1621) in 1609.

Enjoy this stunning performance by The King's Singers, recorded live at King's College, Cambridge.

Monteverdi's Christmas Vespers

When you think of traditional “Christmas music,” you probably think of something with (a) a lot of brass, and (b) a huge choir.

Claudio Monteverdi’s resplendent “Christmas Vespers” features both, in a wide variety of musical styles that, when combined, sound like a quintessential 17th-century Christmas. From celebration to solemnity and back again, these Vespers cover every base.

When Italian composer Monteverdi (1567-1643) wrote them in the early 1600s, the Christmas Vespers — also known as the Vespers for the Blessed Virgin (“Vespro della Beata Vergine”) — were less about Christmas than they were about Monteverdi showing off his hand in writing different styles of church music. He gratefully accepted a new job at St Mark’s in Venice soon after.

That the text and title feature the Christmas story is an added bonus — giving us an annual reason to dip our toes into this piece!

For more about this masterpiece and choosing a recording, see Lindsey Kemp’s review in Gramophone. Although from 2015, Kemp’s commentary provides a nuanced discussion of the context of the piece and a useful guide to choosing a recording.

Silent Night

The real story of "Silent Night" could be made into a happy-ending, made-for-TV movie.

It was Christmas Eve in 1818. The organist and priest at St. Nicholas Church in Oberndorf met. The organ was broken. A snow storm enveloped the Austrian town. The organ repairman wouldn’t make it in time.

Still. Midnight Mass must go on!

What could they do? (The TV version would probably show them looking outside at the falling snow; then zoom in to their faces. A flash of understanding passes between the two — Joseph Mohr, the priest who would share the lyrics, and Franz Gruber, the organist who would compose the music.)

“Here. Use these lyrics I wrote two years ago,” says Mohr.

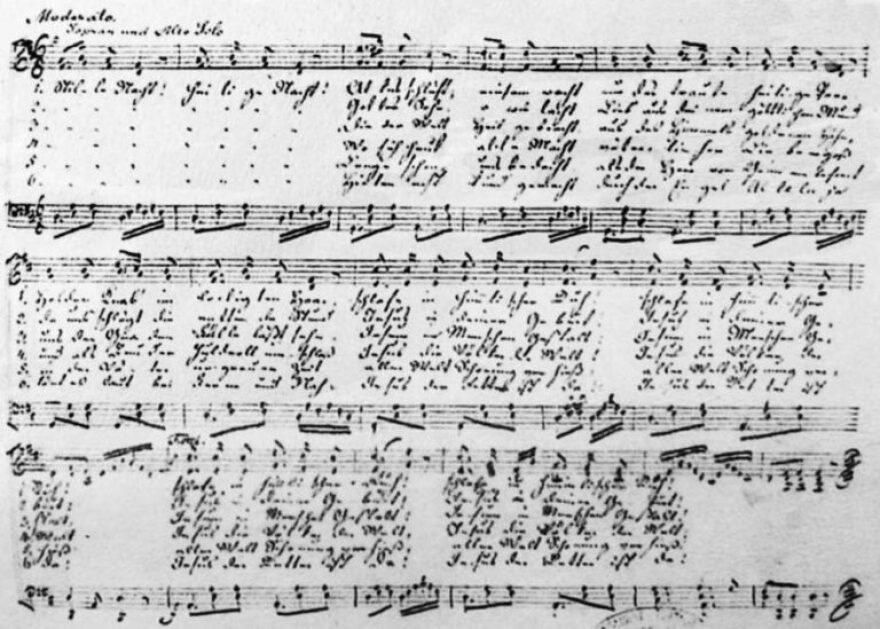

Gruber looks up, taking the text: “Stille nacht, heilige nacht… I’ll compose a melody and harmony–right now!”

And so, that Christmas Eve in St. Nicholas Church, the first singing of Stille Nacht ("Silent Night") rang out, accompanied not by an organ, but by a guitar.

While the exchange between Mohr and Gruber may not have happened exactly like that, we do know that, thanks to this organist and priest, "Silent Night" saved a Christmas Eve, and soon spread across Europe.

Two hundred years later, this beloved carol is sung in over 300 hundred languages on Christmas Eve (often without organ) around the world.

This video by our friends at From the Top pays homage to the classic piece with a new arrangement for four cellos by David Burndrett.