Oh Spring! The flowers are blooming, the birds are singing, and the faithful plodding of a familiar tune can be heard in school gymnasiums, stadiums, and other commencement venues across the country. I’m talking, of course, about “Pomp and Circumstance” No. 1 — the piece that cemented Edward Elgar’s legacy as the English composer.

Here across the pond, Elgar’s work has become a staple of the American education process. If you graduate at any academic level, you might be disappointed if they don’t play this at your commencement ceremony (I was particularly disappointed, since my college graduation was actually a Zoom meeting), but the composer of this familiar tune didn’t always enjoy such a hallowed reputation.

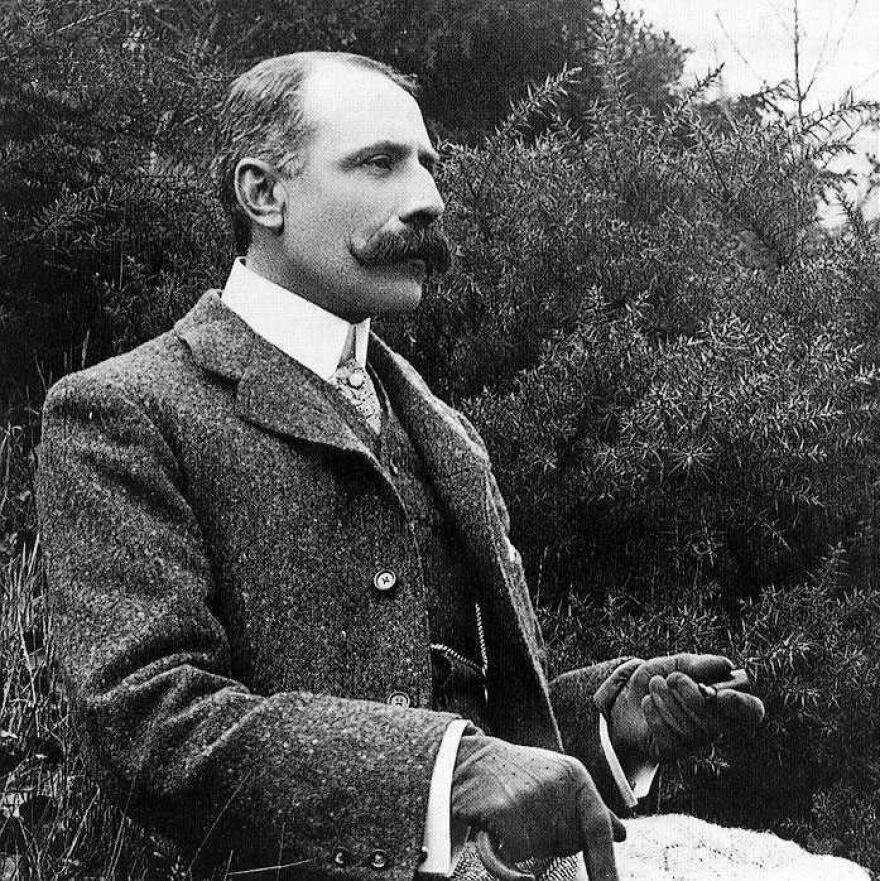

The man, the myth, the mustache…

If you have an internalized image of Edward Elgar already, it probably looks something like this: a stately English gentleman in tweed and leather gloves, with a fashionable cane and a comb-over, and sporting the most voluminous, luxurious mustache to ever grace an upper lip. It’s true that this is the portrait we have been left with, but the composer had much humbler origins.

Elgar’s childhood was a bit less pomp and lot more circumstance. One of seven children, he was born in Worcester, England, to William and Ann Elgar. Much to her husband’s dismay, Ann raised the children Roman Catholic in a time when anti-Catholic sentiment was still quite popular in England. Elgar remained devoutly Catholic throughout his life, despite facing religious discrimination — something that contributed to his lifelong feelings of being an outsider.

William Elgar was a piano tuner and a church organist, an occupation that afforded the Elgar children very little, except the opportunity for musical training. Edward studied piano and violin, and began teaching himself how to play every instrument he could get his hands on. He left school at just fifteen years old to work as a clerk in a law office and never returned to his education. He hated office work and quit within the year, going to work instead for his father — teaching music lessons and tuning pianos, performing whenever he could.

While his contemporaries were studying abroad at illustrious conservatories, Elgar was working the gig economy. In his early twenties, he made a few trips to London to study with acclaimed violinist Adolf Pollitzer, who believed he had what it would take to become a professional violinist. Elgar, however, was already deeply insecure about his own talents and chose not to pursue a violin career. Anyway, he had bigger dreams in mind. He wanted to be a composer.

The wind at dawn

In all likelihood, Edward Elgar never would have achieved his dream if it weren’t for Caroline Alice Roberts. As a published novelist and poet, as well as a musician, she had largely made up her mind to die a spinster. It was a luxury she could afford because of her wealthy family and her own modest income, but something changed her mind when she began taking violin lessons from a young Edward Elgar.

Alice’s family forbade her from marrying Elgar. He was eight years her junior, living in relative poverty, and conducting the ensemble at the local mental asylum. To put it nicely, they considered him beneath her. Alice’s family cut her off financially after their marriage in 1889, and the rejection further cemented Elgar’s own opinion of himself as a social outcast. But it was the income from her writing that gave him the support he needed to fully pursue his dream.

As for their wedding presents, the couple exchanged homemade gifts. Alice gave her husband one of her poems, and Elgar presented her with a short work called Salut d’Amour, which is still lovingly performed to this day.

An English gentleman

Elgar’s marriage did not by any means skyrocket him into success. He spent years struggling to gain recognition, growing increasingly frustrated and despondent. He often found his peers to be dismissive of him because of his lack of formal education. Even as his work gained prominence in certain circles, he felt more and more that he was an outsider. He once coldly rebuffed a dinner invitation by saying he didn’t wish to disgrace his hosts with “the presence of a piano tuner’s son and his wife.”

It's Elgar’s 1899 “Enigma” Variations that finally caught him some of the attention he deserved. The piece is a stunning display of his compositional abilities. In both style and form, it leaves the works of his more studied colleagues in the dust. He began gaining a little bit of confidence. I like to imagine this is where the tweed and magnificent mustache first made their appearance.

Soon after, Elgar began to conceive a piece that showed similar promise to his "Enigma" Variations. It was a brisk military march with a dignified trio that he claimed to have written for the “soldier” in him. He named the piece after a line from Shakespeare’s Othello, “pride, pomp and circumstance of glorious war!” But Elgar certainly didn’t overlook the fact that the pomp and the circumstance of war actually have very little to do with each other. The title is contradictory, and that was intentional. There’s an underlying anxiety stirring in the march, as well as an absurdity that is driven home by several of Elgar’s clever musical jokes.

Still, it was going to be a hit, and Elgar already knew it. He told one of his friends he had a tune that would “knock ‘em flat,” and he was right. When “Pomp and Circumstance” No. 1 premiered in 1901, the audience demanded that it be played twice more. It was an instant hit and was soon adopted as an unofficial British national anthem. Elgar was knighted in 1904, a huge triumph for a man who considered himself to be on the fringes of society.

By this point Elgar’s music had gained attention outside of Britain. He was the first British composer to do so since Henry Purcell (that’s a 162-year gap, if you’re counting) so this was, as they say, kind of a big deal. In 1905 he was invited by his good friend, Professor Samuel Sanford, to receive an honorary degree at Yale. Sanford, knowing his friend would be anxious about the whole affair, decided he would have to roll out the figurative red carpet. Several of Elgar’s works were played during the commencement ceremony, but “Pomp and Circumstance” was the grand finale, a triumphant tribute to a man who hadn’t had the opportunity to continue his education.

After Yale played the march at their graduation, it quickly became fashionable for other Ivy League schools to follow suit. Eventually, the tradition swept across the nation and now you would be hard-pressed to attend a graduation that doesn’t play that “knock ‘em flat” tune. In a way, “Pomp and Circumstance” is Elgar. It’s a piano tuner’s son in the disguise of an English gentleman. It’s the boy who couldn’t scrape together enough money to attend conservatory going on to compose the graduation song. It’s the man who proved you don’t need a fancy degree to achieve excellence.